What Is The Convexity Report? (START HERE)

A Primer For Individuals Seeking To Live Happily In A World They Cannot Understand

A blog called “The Convexity Report” without a post explaining convexity seems strangely incomplete.

Today, we will begin to remedy this oversight by surveying the first of several topics that will serve as the foundation for future posts:

Convexity vs. Concavity vs. Robustness

Mean Reversion vs. Trend Following

Power laws and asymmetry

Expected value - quantifying decisions

Fundamentally, what we’re examining is non-linearity.

Why and how is it that some small inputs generate massive outcomes, while others barely move the needle?

What are the inexorable patterns of The Universe that seem to govern large dynamic systems - from ecology, to physics, to economics - until just as suddenly…they don’t?

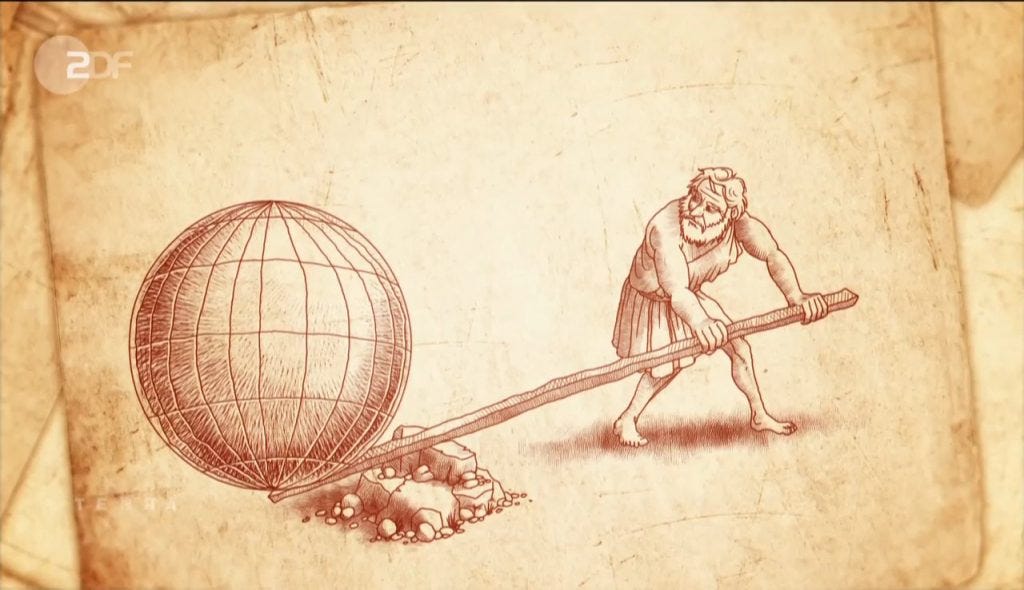

Archimedes once famously said “give me a lever long enough and fulcrum on which to place it and I shall move the world”.

“The Convexity Report” is both a celebration of the lever and the fulcrum. May it inspire you and equip you with the tools necessary to move your world.

Bad News: We Know Almost Nothing About Anything

Fundamentally, systems are a mechanism by which inputs - in the famous words of Donald Rumsfeld: “known”, “unknown” and “unknown unknown” alike - produce outputs.

Enter: Humans.

Humans tend to take a look at the visible inputs, the visible outputs, and construct highly linear narratives explaining the workings of the system that usually bear little resemblance to what “actually” happened.

And any time you hear the word “because” - you can rest assured knowing that this fallacy has almost certainly occurred.

The bathtub fills because you turned the tap.

The vending machine dispenses a soda because you stuck a quarter in the slot.

The stock market is up today because of a statement made by the Recognized Central Banking Authority.

Your company grew top-line revenue this year because of the tireless work of your sales team and the ingenuity of your executives (ok, ok, I’ll stop)

Evolutionarily, the bias makes total sense: Decision making is only possible in the face of certainty, and certainty is only possible in the face of gross and deliberate oversimplification.

You’d probably never enjoy a bath again if your brain went through every single step of what actually had to happen - from the mechanics and history of plumbing to the origin and construction of the specific infrastructure in your home.

Go back and look at the predictive track record of nearly any financial analyst and you’ll find a veritable graveyard of painstaking research - tens of thousands of hours of “research” that ends up being total gibberish bearing no resemblance to what actually ends up happening.

It’s pretty hard to galvanize hundreds of employees and justify massive executive salaries with a rousing speech about how your entire organization is levered beta with expensive commercial real estate and a kombucha bar.

For the most part, things happen around us and we construct a hindsight-heavy “good enough” narrative about the inevitability of the events that transpired, high-five each other, and move on.

At some point we all must confront that what we “know” is dwarfed by the enormity of what we don’t know, which is a mere footnote in the infinite cosmos of what we don’t know we don’t know.

Ironically, none of this is doom and gloom. And if you read it as such then get ready to take the Red Pill.

Good News: We Know Almost Nothing About Anything

What if I told you that you don’t have to know anything to lead a happy, successful and prosperous life?

Even better, what if I told you that you didn’t have to pretend to know anything to lead a happy, successful and prosperous life?

Open your eyes, Neo.

Let’s begin.

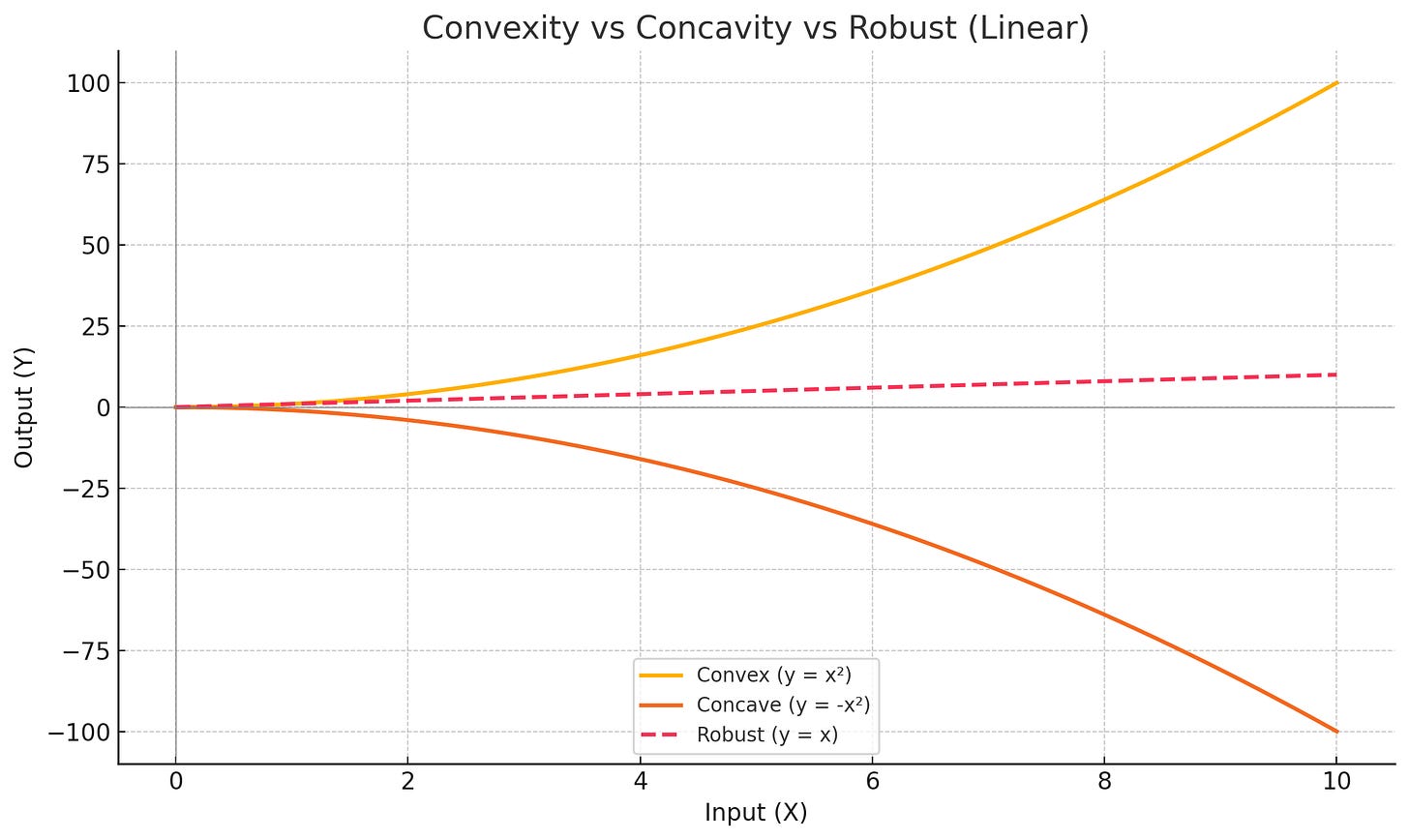

Convexity vs. Concavity vs. Robustness

Ironically, we will have to commit the very sin of oversimplification discussed in the prior section in order to build an actionable operating system. In poker, we call this a “toy game”: By simplifying some assumptions, we knowingly trade off sophistication for clarity. The trick is to make the decision consciously, rather than fool yourself into thinking the world is as simple as your assumptions.

Let’s examine three types of systems you likely see in your day to day life and some general guidelines on how to behave within them.

Robustness

This is the linear world of predictable cause-and-effect relationships. Robust systems exhibit proportional responses: doubling the input results in a doubling of the output. Think of a savings account earning interest, or a manufacturing line where each additional worker produces a predictable increase in output.

Robust systems are characterized by:

Predictable scaling: More effort reliably yields proportionally more results

Limited downside: Losses are bounded and proportional to inputs

Limited upside: Gains are also bounded and proportional to inputs

Stability: Small changes produce small, predictable outcomes

The trade-off? Robust systems offer safety and predictability, but they cap your potential. You'll never lose everything, but you'll also never experience exponential gains.

Convexity

Convexity is a property of non-linear systems that exhibit asymmetric payoffs favoring the upside. In convex systems, you benefit more from positive changes than you suffer from equivalent negative changes.

Think of a startup equity position: If the company fails, you lose your investment (limited downside), but if it succeeds, your returns can be 10x, 100x, or 1000x your initial investment (unlimited upside). The key insight is that convex bets have capped downside and unlimited upside.

Other examples of convexity:

Buying Options: You can only lose the premium paid, but gains are theoretically unlimited

Learning a new skill: The time invested is fixed, but the long-term benefits compound exponentially

Network effects: Each new user makes the platform more valuable for all existing users

Venture capital: Most investments fail (limited loss), but a few generate massive returns that more than compensate

Convex positions love volatility and uncertainty. The more unpredictable the environment, the more likely you are to capture asymmetric upside.

Concavity

Concavity represents the opposite: asymmetric payoffs favoring the downside. In concave systems, you suffer more from negative changes than you benefit from equivalent positive changes.

Consider selling insurance or running a traditional bank: Most of the time, you collect steady premiums or interest spreads (limited upside), but occasionally you face catastrophic losses that can wipe out years of profits (unlimited downside) - Warren Buffett describes this as “picking up pennies in front of a bulldozer”.

For more on how even really smart people can get caught by this trap, Google “Long Term Capital Management”

Examples of concavity:

Short selling: Limited upside (stock can only go to zero), unlimited downside (stock can rise infinitely)

Leverage without hedging: Small market moves against you can trigger margin calls and force liquidation

Reputation-dependent businesses: Years of building trust can be destroyed by a single scandal

Performance bonuses tied to avoiding losses: You get modest rewards for meeting targets, but severe penalties for missing them

Concave positions hate volatility. The more unpredictable the environment, the more likely you are to get blindsided by asymmetric downside.

The Strategic Framework

The key insight is recognizing which type of system you're operating within and positioning yourself accordingly:

In robust systems: Focus on consistency, efficiency, and steady execution. Optimize for predictable, sustainable growth.

In convex systems: Embrace uncertainty, take calculated risks, and position for asymmetric upside. Think like a venture capitalist: make many small bets knowing most will fail, but the winners will more than compensate.

In concave systems: Either avoid them entirely or hedge extensively. If you must operate in concave environments, minimize exposure and exit quickly when things start moving against you.

Conclusion

The universe doesn't operate on our linear narratives. It's a complex adaptive system where small inputs can trigger massive outputs, where cause and effect are separated by time and space, and where the most important variables are often invisible until it's too late.

But here's the silver lining: You don't need to understand the system to benefit from it. You just need to position yourself to capture convexity while avoiding concavity.

This is why Nassim Taleb advocates for "antifragility" – not just surviving uncertainty, but thriving because of it. VCs can’t predict which specific startups will succeed; but they can make enough bets that the winners (hopefully) cover the losers.

Your job isn't to predict the future. Still, you can raise the probability of enjoying it if you can put yourself in a position where small inputs can generate massive outputs, where you benefit more from being right than you suffer from being wrong, and where time and uncertainty work in your favor rather than against you.

In a world of unknown unknowns, convexity isn't just a mathematical concept – it's a philosophy of thriving in uncertainty.

Welcome to The Convexity Report, and may the asymmetries be ever in your favor.

![When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management [Book] When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!x7eQ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6d38dfd2-9c10-438e-867e-13c60f9da2bc_1563x2402.jpeg)